Can AI think? (part 2)

Embodying intelligence and being intelligent

Imagine if on our first manned trip to Mars, we discover an orrery, a mechanical model of the solar system that predicts the positions of celestial bodies. We would be certain that some intelligent being had been there before. This is because the orrery is a small object that reduces the complex movements of these bodies (see part 1) in such a way that is only possible with an understanding of their patterns and interrelatedness. Whether we are examining the sophistication of a machine or the merits of a theory, its intelligence can be measured by its explanatory power and its predictive power. In fact, its predictive power is just proof that its explanation is at least somewhat true. (Speculative theories that predict nothing and which cannot be falsified are difficult to differentiate from fiction.)

What is the precise relationship between intelligence and the orrery? Insofar as it patterns certain underlying structures of the universe, the orrery can explain what we are seeing in the night sky and predict what we will see in the future. If you observe an orrery in action, you will see both of these signs in clear display. We might therefore say that the machine “embodies intelligence.” In some respect, it does not matter who or what made it. From the evolutionary perspective, this embodiment of intelligence is absolutely ubiquitous on earth (and eerily absent as far and wide as we have looked in the universe!). Every creature that exists on earth today is able to live because of how well it embodies the underlying patterns of the environment, whether in its neural network or in its physiology. These underlying patterns include earth’s gravitational force, the composition of air, the behaviors of other organisms, the density of water (notice how perfectly well-adapted the average/overall density of your body is to water so that you can both dive and float), and much more. In a very real sense, the orrery is to the solar system what the squirrel is to the tree. It embodies a thorough understanding in a condensed form. The question therefore is whether this embodiment of intelligence is the same as “being intelligent.”

To begin with, we notice that the orrery does not know that it embodies intelligence, even though it can predict the movements of the stars better than almost anyone on earth. I believe that the same could be said about the squirrel. And the same could be said about artificial intelligence, whose explanatory and predictive powers are beyond anything ever created and yet which still does know anything. Of course, this only pushes the question back further. What does it mean to know? We want to avoid the tangle of unresolvable questions, especially ones that have an inherent circuitousness to them (such as knowing the meaning of knowing). Instead, let us take note of certain clues that suggest that artificial intelligence is something fundamentally different from being intelligent.

Why LLMs need to run code

If you ask a Large Language Model an uncommon question that involves several steps, it may execute code before it responds to you. For example, I asked two LLMs a question. One just happened to use code and the other did not.

ChatGPT - see chat

Grok 4 Fast - see chat

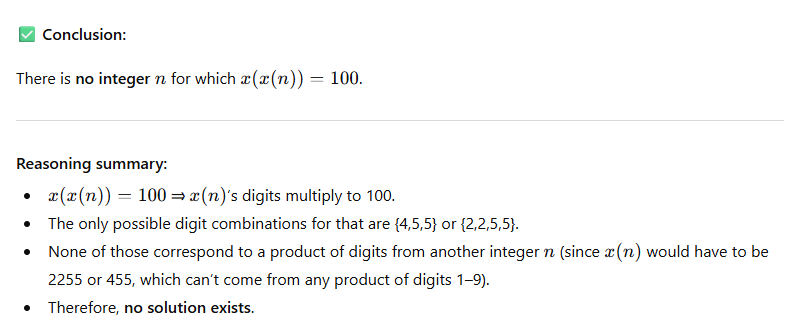

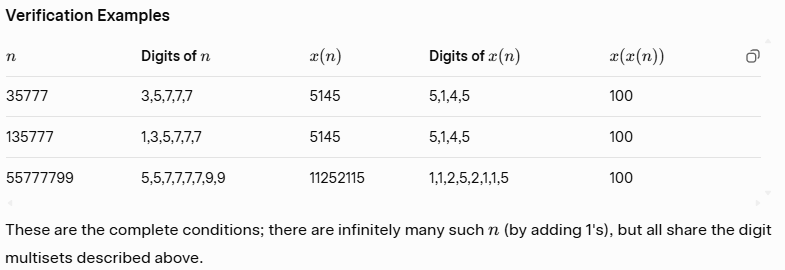

As you can see, Grok arrived at the correct answer, while ChatGPT did not (though it of course employs a tone of finality: no solution exists). Grok solved the problem in part by writing code and executing it. You can view the code by clicking into the link above and expanding the section that says, “Thought for 1m 1s.” This is an important clue about the limitations of AI, at least as we conceive of AI today. A controversial paper published this summer, “The Illusion of Thinking: Understanding the Strengths and Limitations of Reasoning Models via the Lens of Problem Complexity,”1 from a research team at Apple made a similar observation and provided a detailed explanation of when and why code is needed. It was controversial because some in the technology community believe that executing code is “fair game” for an AI model, while others believe that this demonstrates how AI is not truly thinking.

next-token prediction

As far as LLMs have come, it can be easy to forget the basic mechanism on which they are built, which is called next-token prediction. The paradigm of LLMs is this: Given some partial text T (e.g. “The cat is under the”) and based on all existing literature (textbooks, blog posts, Shakespeare, everything!), determine the most probable word that should follow T (e.g. “table”). Try this exact example in multiple LLMs like Grok, ChatGPT, and Perplexity AI. For the prompt, just write “The cat is under the…” You will get the answer “table.”2 If we pause and think about this for a moment, something jumps out at us. “The cat is under the…” has no intrinsic connection to “table” other than the fact that a table is one among the uncountable number of things a cat can be under. From the perspective of understanding, the meaning of “the cat is under” has a negligible connection to the meaning of “table.”. However, from the perspective of literary probability, their connection is very strong: in most of the writing produced by humans, the cat is under the table. LLMs feed back to humans what we would most likely say.3

The significance of predicting next tokens should not be downplayed. Much of human speech and writing is precisely this. Why do experienced public speakers need less time to prepare and yet perform so naturally? How do seasoned writers produce volumes of text while others struggle to write a single paragraph? Fluency is often seen as a sign of intelligence. I believe this is grossly mistaken. Fluency has to do with what LLMs do. Close your eyes and think of a sequence of words in your mind and then abruptly pause. For example: “The world is…” If you pay close attention to your mental activity, you will likely notice the immediate next words almost at the tip of your tongue, perhaps several possibilities simultaneously, even before you think about what it is you are actually trying to say! (Allowing these words to keep flowing rather effortlessly while you are simultaneously thinking about how to direct that flow is perhaps the secret to fluency.) Indeed, many features of what generally passes for “being intelligent” may be merely “embodying intelligence.” In comparison, generating momentous ideas, clarifying muddled concepts, solving new problems, and discerning the minute nuances of a social situation are laborious and next-token prediction will not be of much help. Granted, if like an LLM, we had absorbed all the literature in the world, it might seem easier, but that is only because much of what we would have otherwise considered novel, from this universal vantage point, is not as unchartered as we thought.

Understanding vs. next-token prediction

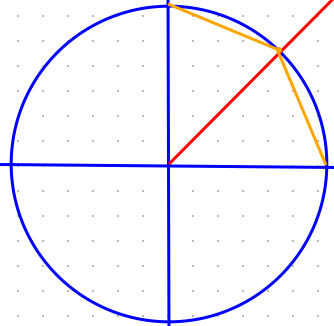

Let us take a concrete example of a human process of solving a problem and attaining greater understanding. Suppose you became curious about how to derive $\pi$ with very high accuracy. ($\pi$ can be thought of simply as the number of miles it would take for you to drive around a semi-circle if your car is always 1 mile from the center.) You pull out a piece of paper and draw a circle intersected by a diagonal line. The exact point of where they intersect, $(\sqrt{2}/2,\sqrt{2}/2)$, can easily be calculated by combining the circle $x^2+y^2=1$ and the line $y=x$ (no cheating by using trig). You connect the points (0,1), $(\sqrt{2}/2,\sqrt{2}/2)$, and (1,1), measure their distance using the distance formula, and voila! You have a first approximation of half of $\pi$, which when multiplied by two, gives you $\approx 3.06$. Not bad!

Here it is on your piece of paper. The length of the orange lines multiplied by 2 is $\approx 3.06$.

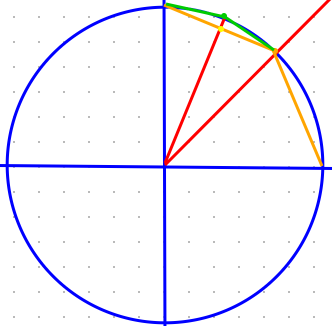

You do it again by perpendicularly bisecting the line from (1,0) to $(\sqrt{2}/2,\sqrt{2}/2)$ whose distance you just measured. Now you get an even better approximation. The length of the green lines multiplied by 4 is $\approx 3.12$. Even closer!

And you keep going… As you sit there and think through this problem, something amazing happens. You start grasping the very meaning of this fascinating number called $\pi$. Where did it come from? How could it be that anyone on earth will discover this exact same, very particular number (3.14159265…) independently of culture, language, philosophy, or religion? Now, you understand it.

After your eureka moment, you go online to see what is out there. It turns out that there are already thousands upon thousands of videos, webpages, and discussion posts explaining how to derive $\pi$. Perhaps the eureka experience (eureka means “I have found it!”) seems insignificant now, since so many others have found it before you. You could have just looked up their algorithms for deriving $\pi$ instead of figuring it out yourself. You could have consulted our all-knowing function $m_0(x)$ or our intelligent function $m_n(x)$. But then you would not really understand it. In fact, at the very best, you would turn out to be just like an LLM - a mere next token predictor.

Using next-token prediction to write code

Because of the inherent limitations of next-token prediction, the creators of LLMs decided to use it to write code. This is remarkably clever. By 2025, the amount of code that is available online, thanks especially to the open source movement, is mind boggling. Grok estimates that there are around 35 trillion lines of code online. Github, a space for sharing code, sees more than 230 new code repositories created per second.4 This gives an LLM everything it could ever need to employ next-token prediction for writing code. It can utilize all the ways that human beings have ever solved problems by writing code. It can also check its own answers, tweak the code, and re-run until it gets the correct answer. This is how Grok solved the question about $x(x(n))=100$ that I asked it above. Since next-token prediction cannot really be called understanding, its use for writing code also appears to be an embodiment of intelligence, a dynamic and adaptable reflection of human genius.

What about the Turing test?

We see the difference now between understanding and next-token prediction. We can see that human beings reason differently than LLMs do, even when LLMs use code. Now we must return to the question of whether this matters or not. In the 1940s, Alan Turing – far ahead of his time – described the criteria by which computers should be considered intelligent, namely that they exhibit (verbal) behavior indistinguishable from humans. It did not matter how they achieved this result or if they thought through a process similar to humans or not, so long as they achieved proper imperceptible “imitation.” He firmly believed that machines would be able to achieve this by the end of the century.

As brilliant as Turing was, his writings about consciousness demonstrate a severe lack of philosophical insight about what it means to be a subject. We are not speaking about a lack of dogmatic or theological knowledge so much as simply a lack of self-knowledge. Arguing for the equivalent value of computers and human consciousness, he wrote, “I think that most of those who support the argument from consciousness could be persuaded to abandon it rather than be forced into the solipsist position.”5 By this, he intended to offer the following argument. Each person can only subjectively know himself. And since we cannot know the subjectivity of others except through their words and behaviors, which a computer could imitate indistinguishably, to deny the subjectivity of computers would be to deny the subjectivity of all others by the same reasoning. Therefore, he saw only two options: accept the consciousness of computers and their ability to think or accept solipsism.

Turing tried to make this argument during his lifetime but it was unconvincing. Over 70 years later, with the brilliance of LLMs and their perfect conversational fluency, one would think that the situation would be different. Not only do we objectively see human-level competence in LLMs but we also have very strong anthropomorphizing tendencies, for example with pets and even in animal research (see Nim Chimpsky). As the renowned cognitive and computational neuroscientist, Anil Seth, stated just a few weeks ago on this topic: “We come preloaded with a bunch of psychological biases which lead us to attribute—or over-attribute—consciousness where it probably doesn’t exist.”6 This is exactly right. And yet, even with such a bias and even though LLMs now embody more intelligence than anyone on earth, we still cannot honestly say that they appear to be subjects. People are more likely to view a monkey as a proper subject than an LLM. This is not because of an irrational bias we have towards monkeys but because being a subject is a real thing that we understand and perceive.7 Yes, LLMs pass the Turing test with flying colors, but their next-token prediction is unlike understanding. Even with chain-of-thought prompts and the execution of code, they are not truly thinking. If there is some other way in the future that AI can achieve true thinking, which seems to depend on knowing and being a subject, apart from the methods we have now, all we can say is that we have no idea what that will be.

Conclusion

Alan Turing was brilliant and thanks to his work and the work of countless others over the last few hundred years, we are privileged to live in a time when machines “embody intelligence” more than most of us ever thought possible. They can already do countless human tasks and they will do more still, freeing us up for higher pursuits in some way analogously to how the industrial revolution freed most human beings from repetitive labor. But had Turing himself digitized all the extant literature prior to his own writings and trained a powerful LLM on it, I do not believe it would have predicted that machines would one day pass the Turing test. Turing did that. Because as incredibly powerful as machines are, from the ancient orrery to the Jacquard machine and now to ChatGPT, they are not capable of “being intelligent.” In the cosmic division of labor, being intelligent is evidently the lot marked out for us.

An LLM is not intelligent, but it is fluent, since it embodies our intelligence in words. Have you ever met a person who speaks brilliantly but on further inspection does not know what he is talking about? Compare that to where LLMs were just a few years ago in terms of “hallucinations.” Humans usually speak at a level commensurate with their understanding. LLMs write brilliantly and convincingly even when they are embarrassingly wrong because there is no understanding beneath the words. The vacuum of understanding is being covered over by the ever-increasing power and scale of next-token fluency. Such sheer power has made LLMs incredibly useful to us, but it will never make them credibly intelligent alongside us.

-

Parshin Shojaee, Iman Mirzadeh, Keivan Alizadeh, Maxwell Horton, Samy Bengio, and Mehrdad Farajtabar, “The Illusion of Thinking: Understanding the Strengths and Limitations of Reasoning Models via the Lens of Problem Complexity,” Apple Machine Learning Research, June 7, 2025. ↩

-

If you do not get the answer “table”, keep in mind that LLMs intentionally add random variation and choose less probable answers to seem more natural. In my trials, I always got the answer “table.” ↩

-

In order to provide more accurate results, LLMs additionally weigh sources by credibility. This is why even very popular texts online (e.g. a misattributed quotation) can be trumped by more authoritative ones that are less common. ↩

-

GitHub - Octoverse: A new developer joins GitHub every second as AI leads TypeScript to #1 ↩

-

Alan Turing, “Computing Machinery and Intelligence,” Mind 59, no. 236 (October 1950): 433–60. ↩

-

Taylor McNeil, “Can AI Be Conscious?,” Tufts Now, October 21, 2025. ↩

-

For excellent philosophical reading on the qualia that differentiate consciousness (i.e. proper subjectivity) from mere functionalism, see David J. Chalmers, The Conscious Mind: In Search of a Fundamental Theory (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996). ↩