Can AI think? (part 1)

1. AI is like and unlike any other machine

1.1 AI replacement is not a new question

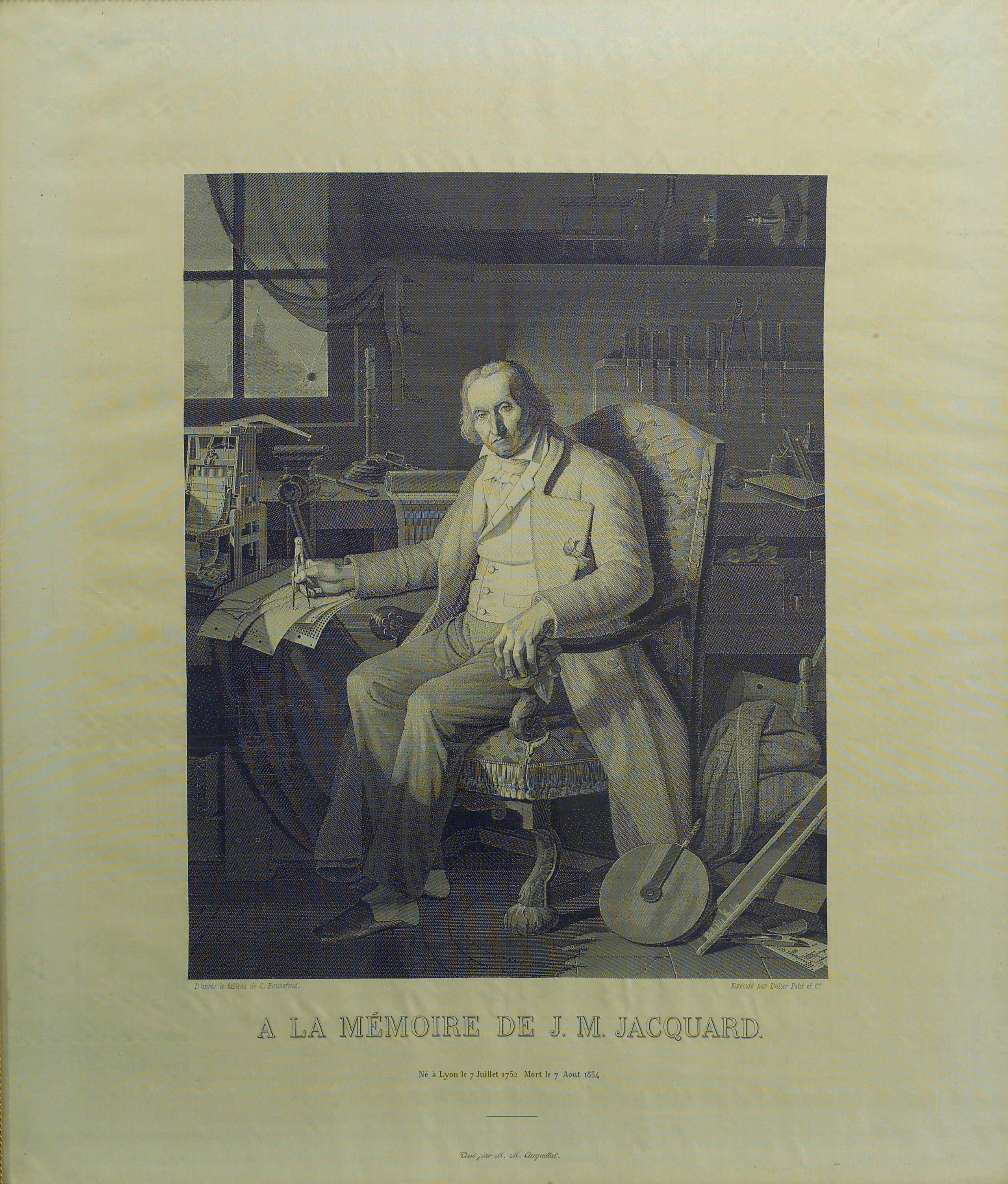

One of the most pivotal questions today is whether AI will be able to replace human beings. To begin with, many human-occupied positions are already being replaced by AI. But this merely proves that some human tasks can be performed well by AI, which in itself should not shock us. We discovered this fact back during the industrial era. In fact, the first programmable loom, the Jacquard machine, was made 225 years ago! Look at this exquisite, silk portrait of its inventor, woven by the Jacquard machine in 1839.

As incredible as the Jacquard machine was for 1801, it is admittedly a long way from where we are today. Could anyone have imagined, before computers and artificial intelligence, that we would be asking this pivotal question today of whether machines can match or surpass human beings? In fact, the very question was asked and answered a full 160 years before the Jacquard machine by the philosopher and mathematician René Descartes in 1637. His answer to the question, with all the excusable limitations of being written almost 400 years ago, proves surprisingly helpful in answering our question.

…although such machines might execute many things with equal or perhaps greater perfection than any of us, they would, without doubt, fail in certain others from which it could be discovered that they did not act from knowledge, but solely from the disposition of their organs: for while reason is an universal instrument that is alike available on every occasion, these organs, on the contrary, need a particular arrangement for each particular action; whence it must be morally impossible that there should exist in any machine a diversity of organs sufficient to enable it to act in all the occurrences of life, in the way in which our reason enables us to act.1

Descartes’ answer is strikingly prescient. He even wrote: “For we may easily conceive a machine to be so constructed that it emits vocables, and even that it emits some correspondent to the action upon it of external objects which cause a change in its organs; for example, if touched in a particular place it may demand what we wish to say to it; if in another it may cry out that it is hurt, and such like.” Yes, in 1637, Descartes foresaw a machine that could tell us using words if it was hurt!

However, there was more than just predictive prowess here. Descartes had insight into the fundamental distinction between machines and humans. He believed that machines, no matter how complex, “need a particular arrangement for each particular action.” Whether the Jacquard machine or a Large Language Model, this appears to be true. The particular arrangement has been growing exponentially complex so that it will eventually become responsive to nearly every scenario (think of self-driving cars or robots, for example). Such rapid complexification would not have been possible without important discoveries made along the way, such as the use of electrons and transistors for processing at rapid speeds, and of course the discovery of artificial neural networks. The mathematical model that we call a neural network was proposed by Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts in 1943 and then first constructed by Marvin Minsky in 1951. The first trainable neural network, called the “Perceptron,” was developed by Frank Rosenblatt in 1957. A trainable neural network is an adaptive and highly nuanced “particular arrangement” of weighted connections between nodes.

1.2 Why does AI work better than manually created machines?

With a sophisticated enough arrangement, a machine can complete highly complex tasks. At the turn of the 20th century, the Pianola, for example, became immensely popular as it could physically play intricate piano songs (without a single electronic component!). Artificial intelligence takes this “machinification” to a new level thanks to trainable neural networks. Unlike traditional machines that need to be given the perfect, particular arrangement in advance, a neural network is able to self-correct its innumerable inner connections through a training process. Eventually, it finds pathways between every stimulus and its expected response. Imagine a domino toppling that makes a phone call. Now imagine a domino toppling that is sophisticated enough to be able to modify its own arrangement as it topples. As Alan Turing predicted in 1950, “By observing the results of its own behavior it can modify its own programs so as to achieve some purpose more effectively. These are possibilities of the near future, rather than Utopian dreams.”2 That is a very rough analogy for a trainable neural network. When the interconnections are represented at the size of modern circuitry and the rearrangements and topplings occur at the speed of modern computation, you end up with unimaginably complex machines adapted to nearly everything.

2. How is AI “intelligent”?

Does this ability to respond correctly to any stimulus constitute thinking? From what we have discussed above, it certainly does not seem to be the case. If anything it seems like an ability for reaction rather than deliberation. The contemporary approach, in this present explosion of trainable neural networks, is to ramp up the number of interconnections and training until the machine reacts as nearly perfectly as possible. In this context, perfection means for any input that is given to it (text, images, audio, video, touch, etc.), it produces exactly what is expected in response to that input. It is like the perfect function $f(x)$ correlating every $x$ to the expected $y$.

Let us embark on a conceptual journey to see whether such a perfect function can be considered intelligent and then whether it has any connection to thinking. To do this, we are going to start with a piecewise function. A piecewise function is any function that looks similar to this:

\[f(x) = \begin{cases} x^2 & \text{if } x \le 0 \\ x^3 & \text{if } x > 0 \end{cases}\]Here, rather than just squaring everything it gets, it has a particular arrangement: it squares whenever x is negative but cubes whenever x is positive.

Now imagine a hypothetical piecewise function called $m_0(x)$ that contained an enormous map from every single question/prompt that has ever been asked by any human being to its expected response. It might look something like this:

\[m_0(x) = \begin{cases} \text{"Proxima Centauri"} & \text{if x = "What is the closest star to the Sun?"} \\ \text{"1989"} & \text{if x = "When was the World Wide Web invented?"} \\ \sqrt{\pi/a} & \int_{-\infty}^{ \infty } e^{-ax^{2}} dx \\ \text{...} \end{cases}\]If it could, in this way, answer every question, could it be said to be intelligent? Most likely not, as this function merely consults a reference table. It is like taking a test with the answer sheet in hand; it does not demonstrate understanding. Now, suppose that rather than mapping every question ever asked to its corresponding output, we found a way to represent these inputs in a large but much more limited number of narrow, continuous piecewise regions, so that, for example, “When was the World Wide Web invented?” and “When was the World Wide Web discovered?” are both processed by the function $m_1(x)$ in the same way. In fact, you could even misspell the words of that question slightly and it would produce the same output, so long as $x$ is not divergent enough to fall outside the domain of $m_1(x)=\text{“1989”}$. Since $m_1(x)$ does not include every single question that has ever been asked, we note that $m_1(x)$ is necessarily less perfect than $m_0(x)$, but it is more realistic to construct.

If we continued to make more reductions to $m_1(x)$, eventually we would end up with some function, $m_n(x)$. Like $m_1(x)$, it does not possess a reference table of every question ever asked and yet could answer nearly every question. It would be entirely realistic to construct because it has been reduced significantly. Moreover, rather being piecewise, it would likely become continuous (over a many-dimensional space). The various regions of the domain would all be blended together at their edges, so to speak. This means that questions with “when” and “discovered” in them would be located in the vicinity of questions with “when” and “invented” in them. And all questions pertaining to the Web would be neighbors in some of the dimensions of this many-dimensional space.

Could this $m_n(x)$ be called intelligent? The question is trickier now. The reductions from $m_0(x)$ to $m_n(x)$ bear a similarity to the mental act of abstraction. In abstraction, we start from discrete, particular phenomena and then recognize underlying commonness. This happens at many levels: semantically, physically, analogically, allegorically, metaphysically, etc. When someone asks me when the World Wide Web was “invented,” I abstract some underlying significance from those words which is the same significance I abstract from the question about when it was “discovered.” Or, we may say, the underlying significations are similar enough to converge upon the same answer. Another special feature of $m_n(x)$, as in any continuous function, is that properties of the question can modify the answer proportionately. If it was asked in Spanish, the output could be in Spanish. If it was asked with a particular tone, the answer could match that tone. This is similar to how a constant factor in the input of a function has some proportionate effect on its output: e.g. $m_n(ax)=bm_n(x)$. These two capabilities, (1) abstracting from particulars and (2) dynamically adapting one’s answers to modifications and qualifications of the question, are typically understood as signs of intelligence. A teacher who wants to measure her students’ real understanding alters her test questions from her review questions. Sufficient alteration will filter out those who merely reproduce answers from memory, and it will identify those who instead grasp the abstract commonalities between the review questions and the test questions. These abstract, nontrivial commonalities are key. Ideally, the test questions are made different enough so that the only semblance they bear to the review questions (i.e. their only commonalities with them) are the underlying truths of the subject matter itself. Grasping the abstract commonalities is therefore equivalent to understanding.

Is $m_n(x)$ superior to $m_0(x)$? $m_0(x)$ has the expected response to every single question that has ever been asked by anyone, which is remarkable. $m_n(x)$ lacks this, but it has something that is better. It can give the expected response to questions that have never been asked before. Its inner logic, gained by compacting $m_0(x)$, bears a certain resemblance to the structure of reality. It is a concise representation of reality, which means that it must contain reality’s patterns qua patterns. It is like when ethologists observe the uncountable movements of millions of bees. The data itself is practically infinite, but they note down specific and finite patterns they observe, such as the waggle dance, which repeat endlessly around the world. $m_n(x)$ must embody the repeatable patterns of reality to be a finite representation of it. If metaphysics makes universal claims about reality, $m_n(x)$ is fully capable of answering metaphysical questions. Its “particular arrangement” will reflect universals and the transcendent properties of being, since these are recurring patterns of reality. Its structure will represent the truth that “causes are always greater than their effects” just as much as it would the movements of the waggle dance.

If all this was not enough, there is one more incredible quality of $m_n(x)$, which is that it does not require $m_0(x)$ in the first place. We formulated it as a reduction of $m_0(x)$, but in fact, because the universe is coherent and consistent (i.e. it follows patterns), only a finite but sufficiently diverse reference table is needed to create $m_n(x)$. This table is called the training dataset.

3. How does AI “think”?

Now, we must turn to our key question. We have just seen how $m_n(x)$ appears to possess intelligence insofar as its inner structure embodies the patterns of the universe and it responds to prompts based on these patterns (not unlike how a sage responds to questions based on timeless truths!). Even still, it does not appear that $m_n(x)$ thinks. Thinking involves steps. It involves considering the various aspects of a problem, breaking it down, reassembling it in new ways, and much more that we do not see in $m_n(x)$. But $m_n(x)$ could be part of a sequence. Its answers could be fed back into itself recursively, with a few helpful meta-prompts to assist, as for example:

- $A = \text{“Why was the Web invented?”}$

- $X = m_n(A)$

#"To facilitate the sharing of information globally" - $B = m_n(\text{“What prompt leads to a more thorough answer than [X] for the question [A]?”})$

#"Also answer the questions implicit in [A]?" - $Y = m_n(B)$

#"It was part of an accelerating movement of worldwide interconnection that began with the telegraph..." - …

If the program ran through several “reflective” steps as in line 3 before producing its output, it would become eerily similar to how we take time to think before we speak. Trainable neural networks are even richer than $m_n(x)$ because, unlike a simple function, they have the ability to return multiple answers simultaneously with varying probabilities of being the expected answer. In the end it chooses one, but these non-chosen possibilities could be used in its internal reasoning steps, so as to pursue different lines of thought along the way. Again, this is like thinking through many angles of a problem before arriving at a conclusion.

Is this recursive process thinking? Is this an elaborate machine that creates the illusion of thinking? If so, could the illusion become so advanced that it lacks nothing in comparison to thinking?

… to be continued in part 2

-

René Descartes, A Discourse on the Method of Rightly Conducting the Reason, and Seeking Truth in the Sciences (1637), trans. John Veitch, Part V, Project Gutenberg eBook #59 (June 28, 1995). ↩

-

Alan Turing, “Computing Machinery and Intelligence,” Mind 59, no. 236 (October 1950): 433–60. ↩