Whether Faith can be Proven

Apparently, there are people out there who think it would be a good idea to test the efficacy of intercessory prayer by subjecting it to clinical trial – so much for “You shall not put the Lord your God to the test.” As one large, triple-blind, and expensive ($2.4 million) study concluded, “Intercessory prayer itself had no effect on complication-free recovery from CABG, but certainty of receiving intercessory prayer was associated with a higher incidence of complications.”1 In other words, they found, while prayers you do not know about have no effect, prayers that you do know about have a reverse effect (perhaps due to performance anxiety)!

Imagine instead that they found a 20% greater likelihood of recovery through intercessory prayer. This would still be problematic. To begin with, what about the other 80%? Andf what does that say about God? Even more, God appears to be merely helping out in these studies, providing some extra boost to what is otherwise a natural process of recovery. If we were going to put God to the test, why not have him do something truly exceptional so as to prove himself beyond all doubt? That is what Sam Harris suggested in a 2007 debate with Rick Warren:

You could prove to the satisfaction of every scientist that intercessory prayer works if you set up a simple experiment. Get a billion Christians to pray for a single amputee. Get them to pray that God regrow that missing limb. This happens to salamanders every day, presumably without prayer; this is within the capacity of God. I find it interesting that people of faith only tend to pray for conditions that are self-limiting.2

These problems arise from a misunderstanding of what prayer is and of who God is. In a scientific experiment, one sets up the proper conditions to stimulate a reaction and then measures that reaction. By carefully ruling out other contributing factors as much as possible, the scientist establishes causation or at least correlation. Thus, I apply heat to water and measure the amount of steam that is produced. In the case of God, however, what would be the proper setup to stimulate a miracle? The experimenters (and all the Christian churches that participated) assumed that it was intercessory prayer. In so doing, they perhaps unwittingly acted as though God were a cosmic force that manifests under certain conditions. These studies are performed by those who believe that reality must be experimentally verifiable. When someone reports a miracle, they are skeptical until they can replicate the results. On the other hand, believers too may covet some indisputable proof that they can flaunt before the modern age, though to do so would require a systematically organized miracle. But this is precisely the point, there is no systematically organized miracle. A miracle is not replicable. If we can replicate it, it is not a miracle—it is nature.

So, the miracle is real but not replicable. It is real but not experimentally verifiable. Is this strange? Only those who need reality to contort itself to fit the methodology of natural science would find it strange. After all, even within the sciences, experimental verifiability is only one kind of method and the certainty attained by it is only one kind of certainty, and they are not intrinsically better or worse than the others.

Certainties in the Formal, Natural, and Social Sciences

Math is Obvious

In mathematics (or the “formal sciences” in general), it is possible to prove theorems. Given a set of axioms, you draw conclusions from them that will thereafter be known with perfect certainty. To take an extremely simple and silly example, we will show that if you have an odd number of ducks, say $N$ ducks, and they each have $N$ ducklings, the total number of ducklings ($N \times N$) will also be odd.

Positive odd numbers are $1, 3, 5,…$ This is equivalent to the multiples of 2 plus 1: $2 \cdot (0)+1, 2 \cdot (1)+1, 2 \cdot (2)+1,…$ Therefore, an odd number $N$ is $2k+1$ for some positive integer $k$ – that is – every positive odd number is one greater than 0 or a positive even number. If $N=2k+1$, we have $2k+1$ ducks and each duck has $2k+1$ ducklings.

\[N \times N = (2k+1) \times (2k+1) = (2k \cdot 2k) + (2k \cdot 1) + (1 \cdot 2k) + (1 \cdot 1) = 4k^2 + 4k + 1\]The two terms on the left $(4k^2 + 4k)$ happen to be divisible by two. If we pull the 2 out, we get $2(2k^2 + 2k)+1$. Notice that $(2k^2 + 2k)$ must be a positive integer, since it involves only the multiplication and addition of positive integers. Suppose we call it $m$, where $m = 2k^2 + 2k$. Now our number of ducks is $N \times N = 2m+1$. This is in fact the very definition of an odd number (i.e. it is one greater than the even number $2m$). Therefore, we know with certainty that, given the contrived scenario above, there will be an odd number of ducklings.

This kind of provable certainty is only possible in the formal sciences, such as math and logic. The theorem that is being proved is in fact a mere re-presenting of the original axioms. Derivations and proofs are about thinking through what was already implied from the beginning. With the help of some visualization, we see how $N \times N$ being odd was already implied by $N$ being odd.

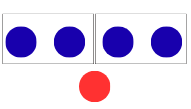

When you try to divide an odd number in two, there will always be one outlier. The number five has two sets of two (in blue) and one odd one out (in red).

If you have an odd number of copies of this odd number, there will be an odd number of odd ones out. In this case, there will be 5 odd ones out (5 red circles).

x (2k+1).png)

$N \times N$ means having $N$ copies of the even parts and $N$ copies of the odd ones out. The even parts are all even and so can be ignored, but when you count the odd ones out, you get $N$, which we already know to be an odd number. In this case, we ignore the blue balls and count the 5 red balls, which makes it odd. This is all remarkably obvious (though still enjoyable!). In fact, everything in math, even the most complicated proof in the world, is just as obvious in principle. The problem is that it is not at all obvious until one sees how obvious it is. And one may not see how obvious it is, for example that $N \times N$ conserves parity, until one thinks about it sufficiently. This leads to the apocryphal joke, told with ever-changing characters:

Comment

by from discussion

inmath

This special kind of certainty, while necessary in its proper domain, is an impossible standard for the other classes of science, as we will see below.

Natural Science is Not False (Yet)

Some people have a field day whenever a prominent scientific theory is disproven. There is a fleeting sense of satisfaction in knowing that even the smart people get stuff wrong. Science can after all be rather intimidating. Everyone is seeking life’s ultimate explanation, and any group that claims to have a monopoly over that enterprise – whether through religion, science, philosophy, self-help, or in any other way – is looked at with fear and suspicion. Science, in its essence, however is unique from the other fields. While individual scientists may be just as egotistical as the next intellectual, science as a whole prides itself on its falsifiability. A claim is not considered scientific unless it can be disproven by an empirical observation. The beauty of this methodology is that anyone can make a scientific claim and anyone else can attempt to disprove it. Over time, this leads to an edifice of knowledge that consists of time-tested theories that have been the most resilient against all attempts to disprove them. The fact that they cannot be overturned suggests that they are the most adequated to the structure of reality. For example, you could attempt to disprove the second law of thermodynamics (entropy) by joining the ranks of countless inventors who have attempted to create a perpetual motion machine over the last one thousand years.

The natural sciences cannot attain the kind of certainty that we see in mathematics. We do not have access to the underlying axioms of the universe. We cannot sit around deriving “obvious” truths that are already implicit in our a priori knowledge. Rather, the universe surprises us in careful observation, and it sends us back to the drawing board over and over again. Yet, the careful work of the last few centuries has paid off. We successfully approximate certainty to such a high degree that we bet our lives on it everyday (e.g. when we travel in cars, take an Advil, or sit calmly at our desk on the 25th floor of a building).

History Never Repeats Itself

The social sciences, unlike the formal and natural sciences, are complicated because they deal with human beings. In some limited sense, they too are falsifiable. For example, a psychologist may publish a paper about how subliminal images influence behavior, and this can be disproven by an experiment involving a large enough sample size. The challenge is that two experiments are never really equivalent. The 1000 people used in the first experiment and the 1000 people used in the disproving experiment could be statistically different. Even if the best measures are taken to have a diverse range of participants, at the very least, 1000 people today are necessarily different (in preferences, common knowledge, etc) from 1000 people 10 years ago. Also, anyone who has conducted an experiment with people (even conducting a survey) knows that quantitative data is often a gross reduction of a many-dimensional problem. (For example, people may rate a course higher because they like the teacher even if they did not learn much.)Experimenters try to resolve this dilemma using qualitative data, but they often end up with quantitative data + anecdotes.

If this challenge is present in psychology, it is all the more present in history. Despite recurring patterns and analogies we draw from contemporaneous experience, history can never be repeated. We cannot verify a theory by empirical observation because the events of the past are no longer at our disposal. We cannot re-run the fall of the Roman Empire thousands of times, tweaking its variables on each iteration, to finally determine whether it was caused by moral decadence or by Christianity, by climate change or by taxes. With psychology, there is at least some hope of conducting a truly objective experiment, but not with history. Is history therefore outside the realm of truth? Is it relegated to the world of subjectivism and fantasy? Of course not. It simply has a different method of converging upon truth and a different kind of resultant certainty. As it turns out, history is one of the most important fields of science, insofar as we learn from our mistakes and build upon the work of those before us. It cannot and should not, therefore, be subject to the standards of certainty employed by the formal and natural sciences. It has its own way of bringing truth to us.

Faith is a Road Never Traveled Before

When a couple who has been married for 25 years recounts their love story, we do not assess its value as truth based on its replicability. In fact, its authenticity as a genuine love story partly depends on its uniqueness and lack of replicability. If a person found their partner in a marriage marketplace, the economic predictability of the outcomes would oppose the mystery of love. This is not just the case with love, but with an individual’s experience of raising their children, of starting a non-profit, or of surviving cancer. Human life never crosses the same path twice. This is why, as much as people desperately search through videos and books that tell you “exactly what to do,” raising children well or making a marriage work never comes easy. The specific, challenging scenarios one is met with on the road of life have never occurred before, and there is no book or human being who can claim to know exactly what you should do.

This “unique path” character is evident in everyday life because of the countless factors involved in any sequence of real events. It is, however, especially evident in the interior life, in one’s spiritual journey. The infinitesimal, interior movements and the vast differences of inner perception between individuals make it impossible for there to be any replicable spiritual path, except in the most general terms. Each spiritual path is unique. Moreover, the ways in which God reveals himself to each individual is also different owing to his infinitude, the unique capacities of each person to reflect aspects of his divinity as imago Dei, and the freedom and mystery of his activity in general.

With all this being the case, what emanates from the human heart in prayer, what unfolds in the dynamism of each person’s relationship with God, the manner in which God acts in time, and the mystery of how he infuses history with his peaceful and salvific reign, escape every form of predictability conceivable. If the most gifted artists and intellectuals in history are known for their consistent originality, how much more is this the case with God, whose “[mercies] are new every morning” (Lam 3:23). The harmonies across his works are observed after the fact and are causes of our amazement but never of our mastery over him. For these reasons, faith is the antithesis of monotony. It is a personal commitment to follow his lead, as one man trusts another with his very life. It is setting out into the unknown, into the ever-greater, with only the assurance of his real presence, alongside us and ahead of us, and the firm conviction of his good will towards us. When we are enmeshed in the quagmire of the predictable, he transfigures our limited perception, overwhelms our capacities, and invites us to the journey of faith, saying, “Rise up, and do not be afraid” (Matt 17:7).

-

Herbert Benson et al., “Study of the Therapeutic Effects of Intercessory Prayer (STEP) in Cardiac Bypass Patients: A Multicenter Randomized Trial of Uncertainty and Certainty of Receiving Intercessory Prayer”, American Heart Journal 151, no. 4 (2006): 934–942. ↩

-

Sam Harris and Rick Warren, “The God Debate”, RichardDawkins.net (republished from Newsweek, Apr. 9, 2007). ↩