What makes the heart so special?

The heart in pre-modernity

The heart is the organ that circulates oxygen-equipped blood cells from the lungs to the other cells of the body. As William Harvey (d. 1657) first observed, the heart is literally a pump, a description embraced and popularized by Descartes. Why has this very mechanical organ, of all the human organs, been used to represent the spiritual depths of the human person?

Our ancestors saw the heart as the seat of emotions, intelligence, and the soul. Today, we comfortably employ what they have written about the heart as though they were speaking just metaphorically. A quick look at what Aristotle said about the heart (and against the brain) will prove otherwise.

These writers… see also that the brain is the most peculiar of all the animal organs; and out of these facts they form an argument, by which they link sensation and brain together. It has, however, already been clearly set forth in the treatise on Sensation, that it is the region of the heart that constitutes the sensory centre.1

He was not speaking metaphorically. He believed that the heart, the physical organ, was the seat of the soul, intelligence, motion, and sensation. He also believed that the brain was meant for cooling purposes. And it is not just Aristotle. Most thinkers down through the ages and across disparate cultures saw the heart as the spiritual and vital center of the human being. (Hippocrates2 was a notable exception, though not the only one).

The Egyptian Book of the Dead of Hunefer describes the the final judgment as a “weighing of the heart.” The image below, painted in 1275 BC, depicts a man’s heart being weighed on a balance. On the other end of the scale is a feather that represents truth, justice, and order. If his heart is weighed down by evil, he will be devoured by the crocodile-headed beast and doomed for all eternity. If his heart is pure and light, he will enter the heavenly paradise.

The Chinese too believed that the heart (Xin) was the source of feelings and thoughts. The same was true in India (hṛdaya). While the Hebrew word “lēḇ” does not point to a specific organ, it generally follows suit by highlighting the ‘heart area’ in general. In the Hebrew Scriptures, “Often lēḇ serves in the absence of a Hebrew word for ‘breast’ or ‘chest’… The lēḇ functions in all dimensions of human existence and is used as a term for all the aspects of a person: vital, affective, noetic, and voluntative.”3

Why the heart?

The choice of the heart across so many cultures must have a reason. Indeed, the heart has special characteristics. It is amazing, for example, how quickly your heart speeds up when you are met with a threat. If you spot a snake on your path, your heart will jump before you realize that you are in danger. Fear, like all emotions, is a “multidimensional” reaction to the environment (or even to automatic thoughts) that can precede conscious awareness. One of the “dimensions” of the fear reaction is your heart rate, which is why your heart rate can clue you in to how you are feeling. Someone says something that makes you angry, your heart rate quickly rises, and then you notice that your heart is pounding and that you need to calm down. Pulse is easily noticeable and helps us recognize how we are feeling. No wonder people use the expression, “I want to feel the pulse of the situation.” And it is also no wonder why the heart became associated with the seat of our emotions, deepest feelings, and conscience.

Of course, there are many other “dimensions” to emotional reactions than cardiac activity. Facial expression, for example, is a powerful indicator of emotion. However, a given facial expression may be the product of the autonomic nervous system (unconscious behavior) just as much as of the somatic nervous system (such as with ordinary affectation). I may smile before others or even to myself though I do not feel happy. Perhaps I smile because I want to feel happy or think I am supposed to feel happy. In that sense, the face can be dishonest. That is not ordinarily possible with the heart, which is why polygraphs are quite effective even on people who can keep a straight face while lying. If a person is in love, even if she does not want to be in love, her heart remains honest with her. If a person is excited, his heart beats faster, even if he tries to appear cool and collected.

Clearly then, the heart stands out among all the organs as the most representative and truthful expression of what one is feeling. It is understandable therefore how it was supposed to be the origin or seat of emotions, morality, decisions, and even thought.

The fine resolution of the heart

Is your heart pounding like a drum? If so, it is probably under the reigns of your sympathetic nervous system (SNS - i.e. fight or flight system), as opposed to your parasympathetic nervous system (PNS - i.e. rest and digest system). Your SNS drives your heart whenever there is need for immediate action, such as when you spot the snake on your path, and your body needs to get high amounts of oxygen everywhere in case you need to run or fight. The PNS comes alive when you are safe and can relax at equilibrium. Remarkably, the SNS and PNS do not just switch on or off in extreme circumstances but have continuous, fine-grained resolution of the heart. In fact, the SNS gets your heart pumping faster every time you breathe in. Ordinarily, assuming you are not under stress, the PNS sends a constant “take it easy” signal to your heart’s internal pacemaker (Sinoatrial node). But when your lungs are stretched, receptors in your lungs keep pinging your brain stem to inhibit the calming effect of the PNS. What results is a mild fight or flight response that triggers the rapid pumping of blood.

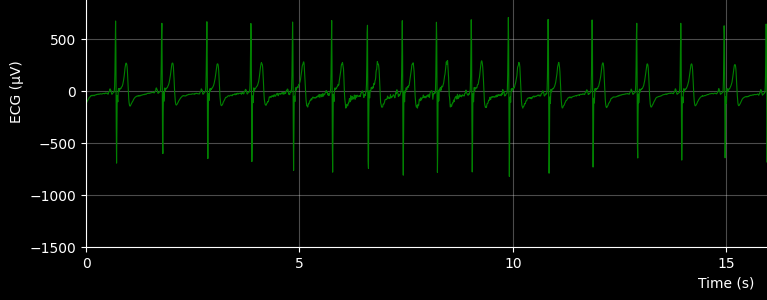

An electrocardiogram records the electrical signals of the heart’s internal pacemaker. The spikes in the following image capture the main pumping action that we refer to as our heartbeat or pulse.

Figure 1 - ECG

Figure 1 - ECG

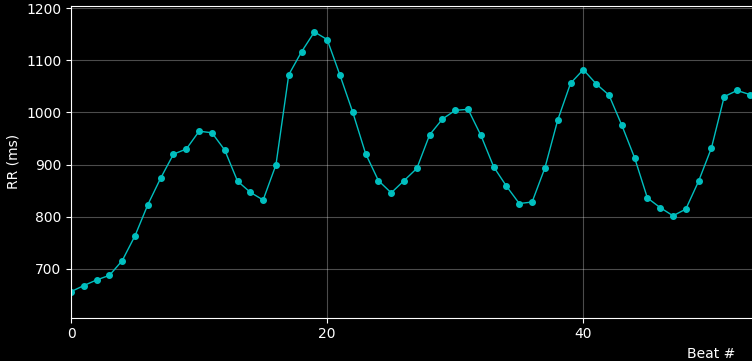

Looking closely, you will see that the spacing between the peaks varies. The time between them is less during inhalation and greater during exhalation. If you assign a time to each heartbeat based on the time lapsed since the previous heartbeat, you will see a curve that moves up and down quite nicely like below. In this graph, the peaks are when the heart is pumping most slowly (i.e. long gaps between heartbeats). It usually occurs at some point while breathing out or while holding one’s breath.

Figure 2 - Intervals between heartbeats

Figure 2 - Intervals between heartbeats

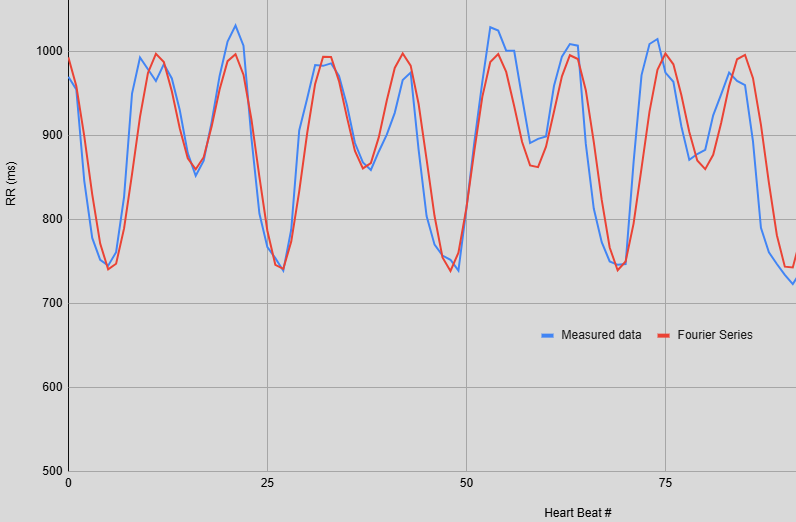

Interestingly, when you first hold your breath, your heartbeat intervals get longer as expected, but after a few seconds, you experience an asphyxiation reflex and your SNS initiates a faster heart rate. If you follow a breathing pattern such as the Weil method (also called “4-7-8”: inhale for 4 seconds/counts, hold for 7 seconds, exhale for 8 seconds), you may notice the asphyxiation reflex at a relatively consistent point in the cycle. In the diagram below, it occurs during the initial portion of the exhalations. However, as your lungs deflate, those stretch receptors stop putting your brain on alert and the PNS comes back in control. In our way of plotting the intervals, this may appear as a dip in the middle of the otherwise rising interval durations. Notice the M-like shape that can occur due to this dip.

Figure 3 - Intervals between heartbeats overlaid with a fitted curve

Figure 3 - Intervals between heartbeats overlaid with a fitted curve

Note: the red line is a periodic, fitted curve to show the remarkable rhythmicity of the heart during a breathing pattern. This wave can be expressed approximately as $r(n)=r_0-\frac{2}{3} s \cdot sin(\frac{2 \pi n}{P})+s \cdot cos(\frac{4 \pi n}{P})$, where $r_0$ is the average interval between heartbeats, $P$ is the number of heartbeats per respiratory cycle, $s$ is some scaling factor (in this case about 100), and $n$ is the variable representing the beat number (not time). Curves will of course look differently for different people and at different times/situations even when following the same breathing pattern. For certain people, (1) the asphyxiation reflex may dip lower and (2) the exhalation peak may climb higher than the holding-breath peak. These two facets can be modeled by (1) adding an inversely-signed, first-order sine wave and (2) phase shifting the original first-order sine wave. It could be represented simply by: $r(n)=r_0-\frac{2}{3} s \cdot sin(\frac{2 \pi (n-2)}{P})+\frac{1}{3} s \cdot sin(\frac{2 \pi n}{P})+s \cdot cos(\frac{4 \pi n}{P})$.

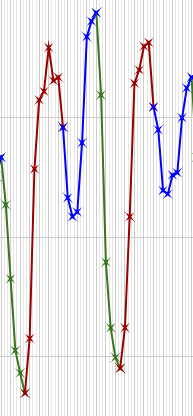

As mentioned above, the dip – the increased heart rate – is caused by the asphyxiation reflex, which, in this case, occurs in the middle of exhalation. (Note: if the breathing pattern involved a longer hold, it would occur during the hold.) This is shown in greater detail below.

In the following diagram:

- green=inhalation: speeding up

- red=holding: slowing down

- blue=exhalation: speeding up and then slowing down

The bilateral arrangement between your heart and your emotions

So far we have spoken about the heart as the bellwether of one’s emotions. The relationship is more complex. Just as the heart rate is partly a symptom of the level of one’s fear or excitement, one’s fear or excitement is also partly a symptom of one’s heart rate. This likely happens through interoception. Your brain senses your heart rate and regulates your felt emotional state. Reducing one’s heart rate can therefore lead to greater emotional calm.4

SNS activation causes your heart to pump at a steady and rapid rate. This is the thumping we may experience when we stand before a large audience or have to confront a loved one, for example. If we could calm the heart, we would feel less anxious, but the challenge is that we do not have direct control over this autonomic function. We therefore take advantage of the close connection between breathing and heart rate described above. Notice how perfectly the heart rate moves in Figure 3 over the course of ~100 heartbeats, so much so that it can be represented by summing a few basic wave equations. Breathing practices like the Weil method, deep breathing, pranayama, and many others aim to bring control to your breath: control your breathing -> lower your heart rate -> reduce your anxiety.

By longer periods of exhalation, you introduce variability into your heart rate. You cause the peaks on the interval graphs to reach higher (more time between beats = lower heart rate). Notice how in Figure 2 the interval moves from ~650 milliseconds (which would equal 92 beats per minute if continuous) all the way to 1150 milliseconds (52 bpm). After a long exhale, you take in a deep breath, causing the intervals between successive beats to rapidly decrease (faster heart rate), and the cycle repeats. This up-and-down elasticity of the heart rate is called HRV (heart rate variation - typically measured by the root mean squared of the differences between successive intervals). Such variability is a healthy sign of greater PNS activation. The SNS, on the other hand, pumps the heart like a steady drum with little variation of heartbeat intervals. This is why lower HRV is strongly correlated with higher anxiety. A meta-analysis found that “Panic disorder (n = 447), post-traumatic stress disorder (n = 192), generalized anxiety disorder (n = 68), and social anxiety disorder (n = 90), but not obsessive–compulsive disorder (n = 40), displayed reductions in HF HRV relative to controls (all ps < 0.001).”5 Through deep breathing or other methods, we aim to increase our heart rate variability and so come to feel less anxious.

Conclusion (for now)

Descartes was not wrong but neither was he right. The heart would have been a mere pump were it not for the unimaginably intricate interconnectivity of the body. The body is a unity, and every organ within it is more than it is by itself. The heart in particular is tightly bound with man’s emotional life and with both his conscious and unconscious feelings and desires. It is therefore an apt symbol for his interiority, for the depths of his being that evade his own understanding.

Our ancestors may not have understood much about the heart or the brain at a biological level, but we are indebted to them for their rich reflections about our interiority. The “heart” gave them a way to name, speak about, and confront these deepest aspects of ourselves which make us truly human. Whenever we are moved by love, pierced by beauty, or touched by God, we feel it in the center of our embodied existence. The heart points us ever-deeper, beyond our visible and social existence, to that place where we lay somehow beyond ourselves, to the image and presence of God within.

The heart is the dwelling-place where I am, where I live; according to the Semitic or Biblical expression, the heart is the place “to which I withdraw.” The heart is our hidden center, beyond the grasp of our reason and of others; only the Spirit of God can fathom the human heart and know it fully. The heart is the place of decision, deeper than our psychic drives. It is the place of truth, where we choose life or death. It is the place of encounter, because as image of God we live in relation: it is the place of covenant.6

References:

-

Aristotle, On the Parts of Animals: Book II, trans. William Ogle, sec. 10. For further reading on this topic, see Thomas Brandt and Doreen Huppert, “Brain beats heart: a cross-cultural reflection”, Brain 144, no. 6 (2021): 1617–1620. ↩

-

“And men ought to know that from nothing else but (from the brain) come joys, delights, laughter and sports, and sorrows, griefs, despondency, and lamentations. And by this, in an especial manner, we acquire wisdom and knowledge, and see and hear, and know what are foul and what are fair, what are bad and what are good…” Hippocrates, On the Sacred Disease, in The Genuine Works of Hippocrates, trans. Francis Adams, sec. 14–18 (c. 400 B.C.). ↩

-

Heinz-Josef Fabry, “לֵב,” in Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament, ed. G. Johannes Botterweck and Helmer Ringgren, trans. David E. Green (Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, U.K.: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1995), 411-412. ↩

-

Nina Bai, “A Racing Heart Drives Anxiety Behavior in Mice, Stanford Medicine Researchers Find”, Stanford Medicine, March 1, 2023. ↩

-

John A. Chalmers, Daniel S. Quintana, Maree J.-Anne Abbott, and Andrew H. Kemp, “Anxiety Disorders Are Associated with Reduced Heart Rate Variability: A Meta-Analysis”, Frontiers in Psychiatry 5 (2014) ↩

-

Catechism of the Catholic Church, “Paragraph 2563: The heart is the dwelling-place…”, in Catechism of the Catholic Church, Part Four: Christian Prayer, para. 2563. ↩