Transcending the Need for Control

1. The Benefits of Control

The need for control is something most of us can relate with. Often people speak of control in negative terms because an almost compulsive need for control of situations can be overpowering and detrimental. Yet, control itself is not bad. In fact, it is the key to navigating, surviving, and thriving amid life’s uncertainties and obstacles. Let us take an obvious example to demonstrate this. When experts predict, with some degree of certainty, that a strong hurricane will make its way to your town, you assume control of the situation by boarding up your windows. In general, we take control to put up a resistance against potential threats. If you have a presentation coming up at work, and you feel nervous about it, the threat you fear is doing poorly, appearing incompetent, or wasting people’s time. You take control by preparing well for it, and this successfully mitigates the risk of failure. Likewise, the body is optimized for control. The immune system, for example, is always prepared for threats. We have B cell and T cell receptors that can identify more than 100,000,000 kinds of antigens (foreign substances). As soon as these cells encounter a threat, the body initiates the process of eliminating it and thus retains control as much as possible.

There are two obstacles to control. The first is uncertainty, which opens us up to risk. As much as we may want to eliminate uncertainty, we can only mitigate it. We can never eliminate uncertainty, as will be shown in detail below. The future is inherently (though not entirely) unpredictable. And as long as there is an unknown future, we cannot perfectly prepare for it. The failure to accept necessary degrees of risk becomes pathological. People suffer from mysophobia (germophobia), for example, when they cannot accept that the risk of germs can only be mitigated but never eliminated.

A second obstacle to control is what we may call recalcitrance. Some situations simply will not be controlled. They will occur as they will regardless of our intentions. This feature of reality has been recognized since the Stoics and is captured in the popular serenity prayer: “God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change…” Two examples close to the human heart are when people wish they could bring back their beloved dead and when people wish they could change the past. In most cases, however, the recalcitrance is not infinite. It may “kick back” (re means “back” and calcitrare means “to kick”) but only so much. Put another way, many recalcitrant situations X do not appear in the absolute form “I cannot do X” but rather in the conditional form “I cannot do X unless I do Y,” where Y is something requiring effort. Even seemingly impossible feats can be conditionalized in this way. “I cannot live on the moon unless I…” As we will see below, one type of control that people expend extraordinary effort on is control over other people.

2. The Certainty of Uncertainty

The first obstacle of control, uncertainty, is much more pervasive and unrelenting than we once realized. 20th century physicists and mathematicians gave us two completely different reasons to be certain that uncertainty is inescapable.

2.1 Chaos Theory

In the 1960s, a mathematician and meteorologist named Edward Lorenz discovered chaos theory. In contrast to the connotations of the name, chaos theory does not imply that the world is without order. Rather, it means that infinitesimally small changes in the present can result in large changes in the future. Insofar as we cannot capture all the infinitesimal occurrences of the present, we cannot predict the future with certainty. Lorenz famously asked, “Does the flap of a butterfly’s wings in Brazil set off a tornado in Texas?”1 This principle is called sensitive dependence on initial conditions. The mathematical equations that model weather patterns (and, as we have since discovered, innumerable other complex systems) exhibit such sensitive dependence.

The double pendulum is a chaotic system that is easier to visualize than weather patterns. Thanks to the open source of work of Erik Neumann, you can try one out for yourself here. In the screen recordings below, you can see that I attempted to drop two pendulums in the exact same way (i.e. with approximately the same initial conditions). They both start off the same, as is typical in chaotic systems. However, the pendulum on the right makes several loops, which the left pendulum never does. Indeed, after the first few seconds of synchronization, they both never move along similar paths again. This is exactly how chaotic systems behave. The infinitesimal (and inevitable), slightest variation in the beginning causes a significant and disproportionate change later on.

Henri Poincaré was perhaps the first person to notice this phenomenon. Here is an except from his “Science and Method” written in 19142:

If we knew exactly the laws of nature and the situation of the universe at the initial moment, we could predict exactly the situation of that same universe at a succeeding moment. But, even if it were the case that the natural laws had no longer any secret for us, we could still only know the initial situation approximately. If that enabled us to predict the succeeding situation with the same approximation, that is all we require, and we should say that the phenomenon had been predicted, that it is governed by laws. But it is not always so; it may happen that

small differences in the initial conditions produce very great ones in the final phenomena. A small error in the former will produce an enormous error in the latter. Prediction becomes impossible, and we have the fortuitous phenomenon.

Our second example will be very much like our first, and we will borrow it from meteorology. Why have meteorologists such difficulty in predicting the weather with any certainty? Why is it that showers and even storms seem to come by chance, so that many people think it quite natural to pray for rain or fine weather, though they would consider it ridiculous to ask for an eclipse by prayer? We see that great disturbances are generally produced in regions where the atmosphere is in unstable equilibrium. The meteorologists see very well that the equilibrium is unstable, that a cyclone will be formed somewhere, but exactly where they are not in a position to say; a tenth of a degree more or less at any given point, and the cyclone will burst here and not there, and extend its ravages over districts it would otherwise have spared.

In his 1950 paper, Alan Turing described the same idea in this way: “The system of the ‘universe as a whole’ is such that quite small errors in the initial conditions can have an overwhelming effect at a later time. The displacement of a single electron by a billionth of a centimeter at one moment might make the difference between a man being killed by an avalanche a year later, or escaping.”3

While chaos theory is a precise concept pertaining to deterministic, physical systems, it is a specific instance of a broader truth. Reality is infinitesimally complex, even while it exhibits comprehensible macro patterns and follows rules well suited to approximation. This infinitesimal complexity cannot be fathomed and so neither can certainty be attained about the future. To apply this notion to another field, think about close relationships. If one were to freeze time during an interaction of two close friends, the nuances of love, thought, perspective, feeling, thoughts about what the other person is thinking, circumstances, etc. are so complex and involved that they are effectively unfathomable. And yet, any one of these phenomena could result in a disproportionate outcome in the future. The smallest and most imperceptible seed of doubt can grow into the end of a relationship just as much as the most fleeting moment of laughter can become the faithful commitment of 60 years. We cannot even wholly know ourselves in a given moment, much less can we know others. Therefore, the future is inevitably uncertain, and its risks cannot be eliminated through control.

2.2 Quantum Uncertainty

Uncertainty at the quantum level rises to a radically new level. Whereas chaos theory practically necessitates uncertainty because of the finite limits of measurement, quantum theory suggests that uncertainty is an essential structure of reality. In the classical understanding, you can observe a particle and know its position precisely. The more precise your measuring rod, the more precisely you can know the particle’s position. However, we have now discovered that, at the atomic scale, determining the precise position of a (free) particle is impossible. In fact, not only can we not determine its position, it appears not to have a definite position. The most accurate way to characterize the position of an atom prior to measurement is by assigning a probability to each position at which you might find the atom if you conducted a measurement. So, for example, I could say that at this very moment there is a 49.99% chance of finding the atom between a and b, a 49.99% chance of finding it between b and c, and a small chance of finding it outside of a and c. There is no way to overcome this uncertainty. It has nothing to do with our capacity for measurement or for prediction. As far as we can tell, the atom itself is not located at a specific position until it is measured.

If we pause and think about what this means, it is troubling. Typically, if you understand the parts of something and how they work together, you understand the whole. In this case, when we break down everything to its constituent parts (atoms, electrons, etc), we find that they lack specificity and definiteness. The answer to the simple question, “Is particle p at position x?” results in a strange answer of both yes and no, or perhaps neither. The same is true about several other properties such as energy level and momentum. It would seem that a universe where answers to the simplest questions concerning its very substance are both yes and no simultaneously should be incomprehensible. Fortunately, this universe of ours built entirely of indefinite blocks is somehow definite. I know exactly where my water bottle is, even though I don’t know where its atoms are.

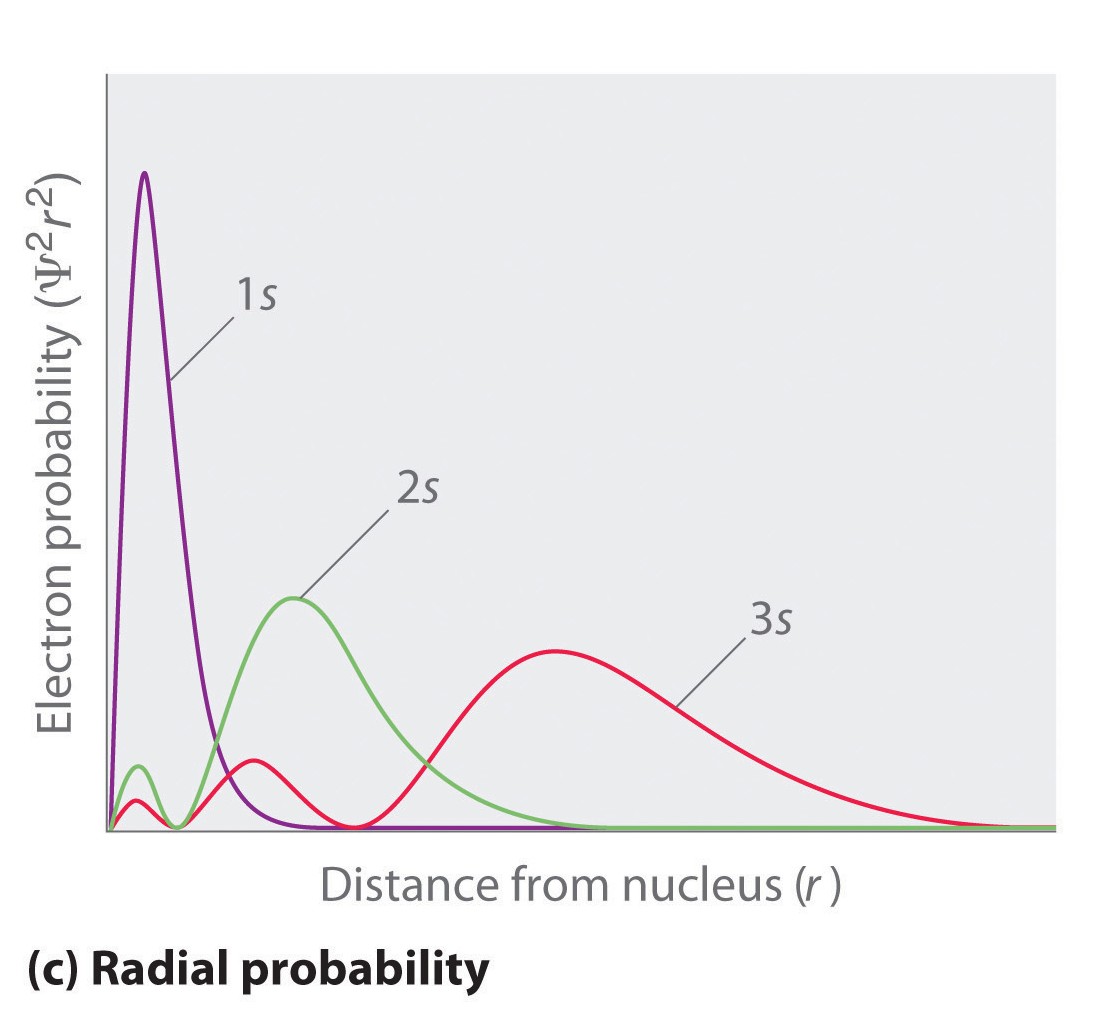

We should note one special characteristic of quantum uncertainty, namely that it is certain. The uncertainty is not unbounded, since we know that all the possible positions of a particle have predetermined probabilities. For example, the electron of a hydrogen atom cannot be anywhere with equal randomness. Its position follows strict laws of probability. The graph below tells us exactly how far a hydrogen atom’s electron can be from its nucleus, depending on its energy level.

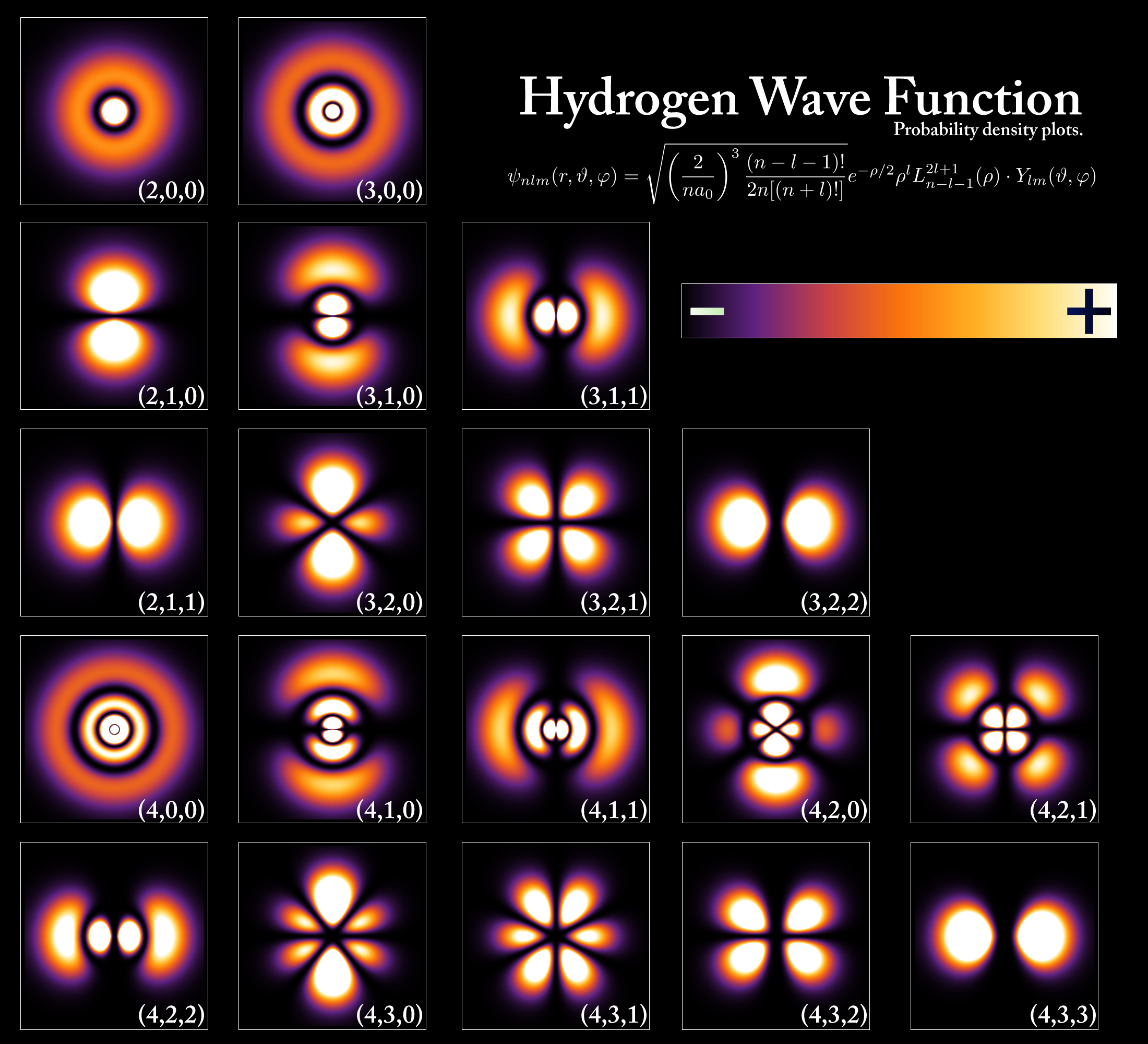

If we graph all the probable locations for where the electron would “appear” if its position was measured, we end up with the following shapes:

Precisely, these graphs mean that if you measured the position of the electrons of millions of hydrogen atoms and plotted their positions together with the frequencies with which they appeared at those positions, you would end up with the images above. Looking at these pictures, it starts to become clear how definite order can emerge from indefinite states. Even if the positions are completely uncertain and unpredictable (i.e. exhibiting true randomness), the uncertainty falls into macro patterns. (In fact, something similar happens with Lorenz attractors in chaos theory, though they are deterministic and not random.)

2.3 Containing Uncertainty

From the foregoing, we see that uncertainty is a certain and inescapable characteristic of the universe. The compulsive need to eliminate all risk is therefore maladaptive to reality (i.e. tending towards pathology). On the other hand, the more precisely we understand uncertainty as uncertainty of some definite kind, we constrain it within a macro pattern, which can be utilized as something certain. We rely on hydrogen atoms, with all their indomitable uncertainty, to act in definite ways and even bet our lives on it when we fly 40,000 feet above the earth in small tubes running on hydrocarbons. The consistent behavior might be an approximation or an averaging out of its randomness. Regardless, uncertainty has contours that be discovered through careful observation and analysis. The wildness of uncertainty can become a tamed wildness.

3. Controlling People

One of the most despised forms of control is the attempt to control other people. This is what people typically mean when they say, “S/he is a controlling person.” All of us can relate to the urge to control others. We may try to control how people think or feel about us. We may try to control the choices (or lack thereof) of our children. Many wise people have pointed out that what other people do is not in our power and that we must learn to accept it rather than attempt to control it. The ancient Stoics, the popular contemporary book “The Let Them Theory” by Mel Robbins, and Alfred Adler’s separation of tasks all point us in the same direction: come to terms with the fact what other people choose to do is not within our control. In that case, we should ask, what ever gave us the idea that it is possible to control another person in the first place? If it is impossible, why do we even try?

Clearly, that other people are not in our control is an oversimplification, albeit a helpful one. Imagine if, as you were taking your children to school, you instructed your son not to taunt his sister for the remainder of the trip. Rather than merely noting whether your words were effective or not (i.e. whether you had control), suppose you opted to take a more scientific approach. Each day, you came home and plotted how many seconds your son refrained from taunting his sister after you instructed him not to. You also included other variables like how many hours of sleep he got and the intensity of your tone. Perhaps you would end up with a graph not unlike the hydrogen density plots above. Such an experiment is of course fictional and even comical. Yet, from this mental exercise alone, we can be sure that a graph of this kind would show us something interesting: we do have control over others.

The control of others is always limited and, in some cases, negligibly small. This is no surprise, since every form control is limited insofar as uncertainty is an inherent feature of reality. There is no way for a mother to be sure which path her child will take, despite her best efforts. And yet, for all its limits, we cannot reasonably deny that the mother exercises some degree of control over her child and that the outcomes of her parenting likely follow a probability distribution. If they did not and the outcomes were as good as random, parenting would be pointless. The same of course is true in all relationships in varying degrees and with special probability distributions of their own.

3.1 The Need for Power

We can modify the previous parenting experiment. Instead of tracking just your child’s compliance to your instructions, you could track everyone’s compliance. You could even make it recursive so that if person A has a 50% chance of complying with your instructions and person B has a 50% chance of complying with person A’s instructions, person B can be said to have a 25% chance of complying with your instructions indirectly. This imaginary probability distribution, with all other particular variables added, is a first draft representation of your power.

To make the model complete, we must factor in the extent to which you yourself are controlled. A traditional king was very powerful, except when he was a vassal or a puppet (i.e. if he had to comply some 90% of the time with the larger empire). Even though many people followed his instructions, he was not powerful per se. We would have to think of your power, then, very roughly as how much you control others minus how much you are controlled by others. By this definition, an inordinately powerful person is one who can tell anyone what to do and they will do it, while no one dares tell him what to do. Such a description happens to coincide with the common sense perception that powerful people can “do whatever they want.”

People seek after power even at great personal cost. This is because increased control over others helps mitigate the risks posed by uncertainty and mobilizes collective effort against reality’s recalcitrance (as defined above). Power makes a person feel secure and capable without the need to appease others (i.e. without making concessions) for protection and support. A person that no one listens to or cares about, a truly powerless individual, has very little opportunity to mitigate risk. He is susceptible to every form of attack that could have been prevented through the support of others, such as illness (since medical treatment requires the services of others). The truly powerless man is necessarily poor, since money is a form of power, insofar as others will do one’s bidding in exchange for it.

The assumption that people pursue power at great personal cost to mitigate risk and overcome obstacles may seem doubtful. It is often supposed that people pursue power to be able to do whatever they want and get whatever they want. This is true, but the same may be said for everyone. Everyone wants to do what they want to do. That is a tautology. Everyone wants to get what they want, by definition. The problem is that there are obstacles and threats that get in the way. Power minimizes the resistance posed by obstacles. Power is ability (δύναμις, potis) through control of others. It does not mean merely being able to break rules, laws, or social conventions. Power means being able to see the stars from above the atmosphere, to learn the piano from a maestro, to start a large nonprofit that transforms the lives of entire populations, to travel for months learning about ancient history, and doing whatever else one’s heart may desire. It is no surprise, then, that studies show that powerful people are happier. At least one study demonstrated a similar conclusion as ours, that power is desirable precisely because it diminishes threats. In the authors’ words, power makers people happier because it “activates proactive coping strategies,” which are defined as “one’s cognitive and behavioral efforts to control, resist, and mitigate the internal and external demands of stressful events.”6

Though all people want what they want, only some people seek power to obtain them. There are many reasons for this. In some cases, it may be mere self-protection (i.e. cowardice), which is another form of control. In certain other cases, however, there could be a far more important reason at play, which is explored below.

3.2 The Paradoxes of Power

3.2.1 Love and Power

By definition, having absolute control over others mean that they follow all your instructions. However, it does not mean that there is control over their interiority: their thoughts, feelings, aspirations, and their heart. This presents a special problem in the case of love. Even assuming it were possible to make a person love you, they would only be following your orders in doing so. It would be a behavioral love, an animal love, but never love from the heart. When you make someone love you through power, you are merely loving yourself. Men have been doing this all throughout history, not excluding paying for “love.” However, if you use power to obtain love, you forfeit the greatest happiness of all, which is to be loved for who you are. This problem is captured well in the mythological notion that a genie can grant almost any wish that your heart may desire but never that wish which your heart most desires, which is to be loved. The genie is helpless here, as all powerful people are, because to make someone love you is a contradiction in terms.

So far, we were thinking of love in the sense of an intimate relationship. In leadership, love takes on a different form but follows similar rules. Many kings and queens, CEOs, presidents, politicians, billionaires, and religious leaders try to make others love them by way of power. In doing so, they too merely love themselves. For this reason, they find that the praises are never enough. After all, nothing that is ingenuine can be enough. They gladly receive people’s appreciation hoping that it will satisfy their need for love but simultaneously knowing that none of it is real. Jesus warned his disciples about such people, saying, “Beware of the scribes, who like to walk around in long robes and like greetings in the marketplaces and have the best seats in the synagogues and the places of honor at feasts, who devour widows’ houses and for a pretense make long prayers” (Mark 12:38-40).

As has become clear, love cannot coexist with control. Love requires that we venture into a space that is characteristically outside of our control. It exposes us to risk and makes us vulnerable. This is why even the wealthiest people lose unimaginable sums of money in acrimonious divorces. These most powerful people of the world, who have everything securely fastened in their lives, lose all control in the arena of love. They powerfully fended off threats from every side, but in love they were powerless. Perhaps later in life, in their second and third marriages, they will go in with all manner of legal protections in place, proportionate to their disenchantment and inability for love. This too proves that love and power cannot exist. The first paradox of power is that, though it is sought for happiness, power is antithetical to love, which offers the greatest happiness of all.

3.2.2 Leadership and Power

If you are someone who inspires others, there is a high probability that others will follow your instructions, and yet this is not control. When a person chooses to do something freely (i.e., if they are inspired), they are not being controlled by you but by themselves. In fact, power (one’s control over others minus one’s being controlled by others) shifts its weight whenever you inspire someone. The other person’s power increases as yours decreases. Imagine a person who is genuinely loved by a great number of people. She is, for example, a mother but one who reverences the individuality and particular dignity of her children. She is a CEO but one who sees her employees as autonomous collaborators rather than as her servants.7 She is a wife but one who has no desire to control her husband but only to allow him to flourish in his own right. In all such cases, she relinquishes control and opts to inspire rather than coerce. Through gentleness (i.e. reverence concerning the otherness of others), she finds great fulfillment and even the greatest possible support. People stand by her but only because they want to.

When you control others, they cannot be inspired by you. A leader is one who, in part, frees, enables, and inspires others to follow their genuine aspirations and then hopes for the best possible outcome. This non-controlling form of leadership is a vast topic that must be developed further elsewhere. Nevertheless, the second paradox of power is that you cannot become a great leader until you let go of power.

3.2.3 Security and Power

Powerful people usually carry an air of indestructible confidence. It is strange therefore that, with many of them, the smallest criticism can send them into a rage. Slight challenges to their sense of superiority can be met with tantrums and vengeful scheming. Such explosive reactions are obviously symptoms of acute fear. The third paradox of power is that power makes people insecure about losing their power.

The security obtained through control, which we explored at the outset, is evidently a fragile security and not a secure security. It is like a massive, protective structure made of glass. It protects you, but it can be shattered in any moment. On the other hand, there are those who find security apart from control and who have a firmer basis for it. They are not afraid of uncertainty. Rather, they can embrace it because they possess a mysterious certainty that underlies the uncertainty. This certainty is called faith, and we can see it in plain sight in a figure like Paul, the apostle of Christ, who in his letter to the Philippians wrote:

I have learned, in whatever situation I am, to be content. I know how to be brought low, and I know how to abound.

In any and every circumstance, I have learned the secretof facing plenty and hunger, abundance and need.I can do all things through him who strengthens me(Phil 4:11-13).

Faith, in the Christian sense of the word, means entrusting oneself to God through Christ. On this basis, Paul finds that he “can do all.” (This is a powerful stance, though not a controlling one. Using “powerful” in this way would require us to relocate the signification of “power” to its more primitive meaning as ability. For the purposes of this essay, we refrain from doing so and maintain the more common usage pertaining to control over others.) Paul’s faith gives him extraordinary ability without control. He entrusts himself to “him who strengthens [him],” knowing that he “works all things for good for those who love God” (Rom 8:28).

4. Conclusion

The desire for control is one of the most natural responses to the inherent uncertainty and recalcitrance of the universe. However, even when this desire is heeded in non-pathological ways, it can result in significant trade-offs of higher goods, such as love, inspirational leadership, and secure security. Such transcendent goods lie at the intersection of matter and spirit because they cannot be wholly explained by material causality. When people seek them out, they relinquish control, not to fall back into the primordial chaos from which control saves us, but to ascend to an even higher order of certainty through faith. This order governs the spiritual destiny of mankind, and those who pursue it carry the world forward.

-

Edward Lorenz, “Predictability: Does the flat of a butterfly’s wings in Brazil set off a tornado in Texas?”, 1972. ↩

-

Henri Poincaré, “Science and Method”, 1914. ↩

-

Alan Turing, “Computing Machinery and Intelligence,” Mind 59, no. 236 (October 1950): 433–60. ↩

-

LibreTexts Chemistry. CH185: General Chemistry (Ragain). ↩

-

PoorLeno at Wikipedia English, Hydrogen Density Plots. ↩

-

Hyun, S., & Ku, X. (2020). How does power affect happiness and mental illness? The mediating role of proactive coping. Cogent Psychology, 7(1). ↩